“And I keep hittin' repeat-peat-peat-peat-peat-peat”: A look into repeat expansion disorders and their impact on the brain and body.

Have you ever had your phone glitch while you’re typing, where the letters keep repeating and what you meant to say gets completely distorted, and the message no longer makes sense? That’s a bit like what happens in repeat expansion disorders. In our DNA, a short sequence of letters that make up our genetic code,like CTG or CAG, may be copied too many times. Just as the repeated letters on your phone mess up your text, these repeated genetic sequences can disrupt how a cell reads and carries out its instructions. These expansions can lead to a variety of neurological and muscular symptoms.

Many neurological and neuromuscular disorders arise from repeated DNA sequences known as repeat expansions that interfere with normal cell function in different ways. In Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1), repeated CTG sequences in the DMPK gene cause toxic RNA to accumulate inside cells and disrupt normal messaging, leading to muscle stiffness and weakness and, in some cases, learning difficulties. Myotonic Dystrophy Type 2 (DM2), caused by repeated CCTG sequences in the CNBP gene, shares similarities with DM1 but is typically milder, mainly causing muscle pain, weakness, and stiffness. Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) results from repeated CGG sequences in the FMR1 gene, which silence a gene essential for brain development and lead to learning and behavioral challenges. In Spinocerebellar Ataxias (SCAs), repeated CAG sequences in various genes damage brain regions responsible for balance and coordination, resulting in movement difficulties. ALS and Frontotemporal Dementia linked to C9orf72 arise from GGGGCC repeats that generate toxic molecules, harming nerve cells and causing both muscle weakness and cognitive changes. Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy (Kennedy’s Disease), caused by CAG repeats in the AR gene, primarily affects men and leads to muscle weakness and hormonal changes. Finally, Huntington’s disease is caused by CAG repeats in the HTT gene, resulting in progressive damage to brain cells involved in movement, mood, and cognition. Together, these disorders highlight how repeat expansions across different genes can profoundly affect both the brain and the body.

Among these conditions, Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1) stands out as a complex and still underexplored disorder. Unlike many repeat expansion diseases that primarily affect one organ system, DM1 is a multisystem condition impacting muscles, the brain, heart, and digestive system. In healthy individuals, the DMPK gene contains fewer than 35 CTG repeats; in DM1, this number can expand to hundreds or even thousands, with longer repeats associated with earlier onset and more severe disease. These expanded repeats produce toxic RNA that interferes with how genes are processed and how proteins are made, particularly in muscle and brain cells. As a result, individuals with DM1 may experience muscle weakness and stiffness, fatigue and excessive sleepiness, difficulty with attention and memory, and serious complications involving the heart and breathing. DM1 is progressive, meaning symptoms worsen over time, and there is currently no cure. However, ongoing research aims to understand how this toxic RNA causes cellular damage, with the goal of developing therapies that target the disease at its root rather than only treating symptoms.

Photo by Mohamed Nohassi from Unsplash

Historically, DM1 research has focused largely on muscle dysfunction. Increasingly, however, evidence points to the brain as a major site of disease involvement. For instance, a brain imaging study revealed changes in white matter (the wiring of the brain) and loss of brain volume in DM1 patients. At the cellular level, studies using mouse models have shown that the toxic repeats in DM1 disrupts proteins that help neurons function properly. Together, these findings underscore the importance of understanding DM1 not only as a muscle disease, but as a disorder that significantly affects the brain.

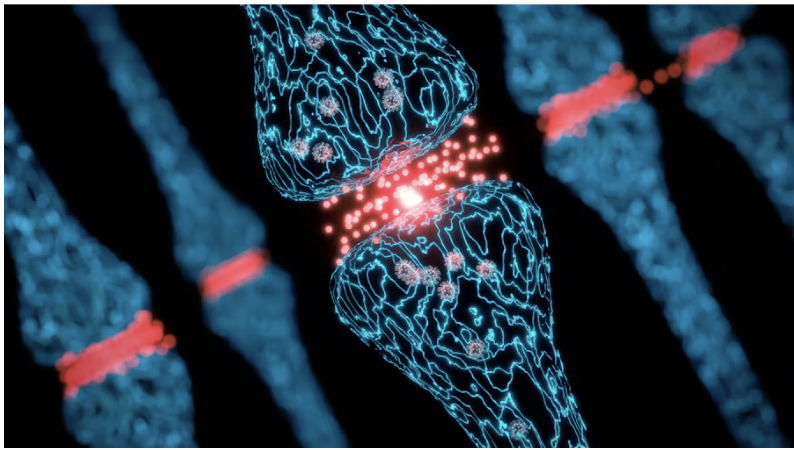

Several researchers at Emory University study repeat expansion disorders. Gary Bassell, Ph.D., professor and chair of Department of Cell Biology at Emory University, examines how these repeated sequences cause changes to protein synthesis in brain cells, particularly at the site of chemical release known as the synapse. At the synapse, one brain cell releases chemical messengers that the next cell receives. This process is what allows us to think, move, remember, feel emotions, and learn.

“For more than 20 years, I’ve been fascinated by genetic causes of synaptic dysfunction that lead to behavioral outcomes” says Dr. Bassell. “My journey of studying repeat expansion disorders started at Albert Einstein College of Medicine where my lab studied how tiny structures on brain cells called dendritic spines are altered in Fragile X syndrome. My lab later expanded to study myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) after I met Eric Wang, PhD, professor at the University of Florida, who invited me to apply my expertise to another repeat expansion disorder.”

Betty Bekele (left) and Gary Bassell, Ph.D. (right) at the 2024 Society for Neuroscience Conference in Chicago, sharing their work on myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) with the larger neuroscience community.

The collaboration between the two investigators has led to important advances in our understanding of how repeat expansions can disrupt the normal function of proteins in nerve cells. Understanding these complex effects is crucial, and the general public can play an important role in advancing DM1 research. Supporting patient advocacy organizations such as the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation, participating in clinical studies, donating to research, and raising awareness about the condition all help accelerate scientific understanding and bring potential therapies closer to patients.