A scientist’s quest to unlock the potential of mRNAs in brain science

Dr. Sulagna Das, Ph.D.

Have you ever wondered how memories are stored in the brain? Or more specifically, why is it that you can always remember that 1+1=2, but you always seem to forget the capital of California, even though you’ve probably been taught or exposed to this fact more than once? (It’s Sacramento, by the way!)

Dr. Sulagna Das (Photo courtesy: Dr. Sulagna Das)

These questions have been of great interest to many researchers across a multitude of fields for a while, but few are tackling them in the same way as Dr. Sulagna Das, Assistant Professor in the Department of Cell Biology at Emory University School of Medicine. Dr. Das’s research is at the intersection of RNA biology and neuroscience. She says that her lab is mapping the RNA life cycle in healthy neurons [so] we can understand what gets disrupted in diseases. Her lab is specifically interested in the role of mRNAs in memory formation and storage, with a focus on neurological conditions like Fragile X Syndrome (FX) or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

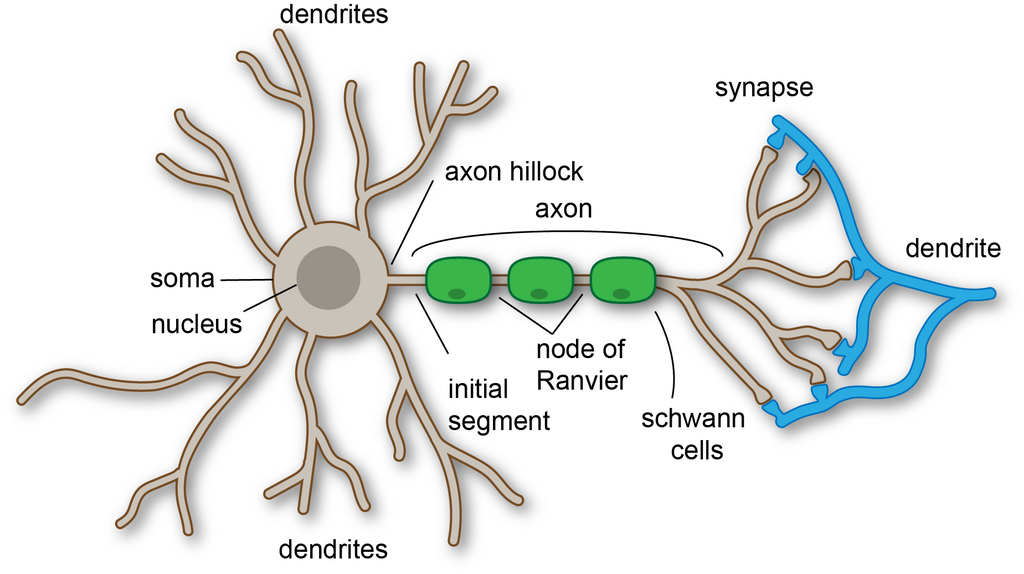

Put simply, memories are connections formed between neurons at junctions called synapses. Together, these synapses form a wide interconnected network that becomes strengthened as they are continuously exposed to an activity or idea, making for better memory. This process called “synaptic plasticity”, ultimately sets the foundation for learning, memory, and adaptation.

On a molecular basis, mRNAs are molecules central to life. Our genes, encoded in DNA, are made into RNAs or words that can then be made into proteins or sentences. The making of RNAs, called transcription and conversion to proteins, translation are crucial players for memory formation and storage. Termed “inducible” genes, these mRNAs travel to synapses once synthesized during transcription, where they are locally translated into proteins that are critical for memory formation and storage.

Despite our knowledge of these RNAs, many outstanding questions remain: How do these mRNAs travel hundreds of microns away to arrive at their proper synapses? Are these mRNAs shuttled together, protected from the enzymes that could easily chew them up along the way? Moreover, what are the cues for their local translation, and how do these proteins actually influence memory?

“A lot of [these RNAs] function at the synapse to change the structure and stability of the synapse, so if you get dysregulation of RNAs, these connections are not stable anymore”, says Das. “But that “our memory is really driven by these stronger and more stable connections, especially long-term memory.”

Anatomy of a Neuron on Wikimedia Commons

The ultimate goal of the Das laboratory is to produce cutting-edge technology that can track these inducible mRNAs in real time, from their production all the way to their transportation and translation within neurons. Her work specifically uses real-time imaging with highly advanced microscopy techniques to watch an mRNA’s lifecycle progress to get a sense of what’s happening to them over time. “We have chosen three or four of these mRNAs, and at least what we have found, is that they are being subjected to unique regulation”, further complicating the picture.

The cyclical regulation of these mRNAs is reminiscent to our circadian rhythm: this is an intriguing trend that Das has noticed throughout her work. Just as you likely do not want the constant release of melatonin to keep you sleepy all day, certain neuronal RNAs are also tightly controlled and activated only under specific conditions.

She first noticed this trend during her post-doctoral work studying a specific inducible gene called Arc, which is critical for long-term memory formation and implicated in several neurodegenerative and cognitive disorders.

“This [Arc] transcript is very unstable; it gets degraded within an hour or a couple of a hours,” says Das. “So how is it possible that this very small, unstable transcript can influence a process such as over several hours or days?” Curious about this gene’s short but powerful lifespan, Das spent eight hours at a time imaging Arc.

Previous research shows that “the gene turns off after two hours and researchers don’t see any transcription. “But if you follow it long enough, you see reactivation of the gene and the gene keeps oscillating over time”. Over the eight hours, she could see three cycles of oscillation, but she notes that she likely could’ve seen more of these events if not for microscopy limitations.

Photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

“I was blown away” says Das. “This idea of transcriptional cycling I think was really novel and has not been identified for any of these genes”. She speculates that maybe these processes are similar in nature to the same ones that drive memory formation: potentially, repeated expression of these proteins helps create and store memories at the synapses. Her findings on Arc can be described as her “aha!” moment that strongly drove her ambition to continue down this field of untangling this complex but harmonious network of neuronal RNAs critical for proper brain function.

Now as she reflects on her path, Das says her journey to reach her position at Emory was not straightforward. Her science career started in India where she studied physiology for her undergraduate degree, followed by a master’s in biotechnology, where she was introduced to molecular biology and where she fell in love with the nervous system. Because of this, she decided to pursue a PhD in neuroscience, specifically studying an encephalitis virus that inflame the brain on a cellular and molecular level. In the later years of her PhD, she attended a microscopy workshop, where she became utterly fascinated with the power of super resolution imaging which caused her to dramatically pivot her research interests.

“Her findings on Arc can be described as her “aha!” moment that strongly drove her ambition to continue down this field of untangling this complex but harmonious network of neuronal RNAs critical for proper brain function. ”

After her PhD, Das immigrated to the United States to search for a post-doctoral position. As she transitioned to a completely new field–live imaging–Das explains that she experienced difficulty finding a position since she had not built up a strong network or base to back her up in this new research area. Nevertheless, her perseverance, scientific caliber, and numerous publications spoke for themselves, leading her to complete two post-doctoral positions in the live-imaging fields. In her first, she brought the biology to a physicist, doing a lot of protein and cytoskeletal imaging where she zoomed into the proteins of the cells’ insides. Her second post-doctoral mentor, Dr. Robert Singer, a prominent pioneer in the RNA imaging field at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, introduced her to the RNA. Here, she contributed a lot of her neuroscience background to set a strong foundation for her independent research career.

She later encountered difficulty again while seeking a faculty position due to COVID-19 and hiring freezes. Despite the obstacles, Das always dreamed of having her own lab, so she persisted just as she had learned to do throughout her science journey. She finally joined Emory’s Cell Biology Department in January 2022.

Lab group of Dr. Sulagna Das (Photo courtesy: Dr. Sulagna Das))

When asked to give some advice for young researchers who are beginning their career in science, Das says, “Keep that passion growing, spend time in the lab, try out experiments; it’s the best time for failed experiments”. She says that the early years are the best times, that’s the time you can be the most excited about science and to read up as much as possible because you are entering the field. Das strongly believes everyone’s journey is so unique and to carve your own path.

Even as a Principal Investigator, Das continues to spend time in the lab herself, saying that people have to sometimes kick me out so that I don’t hog their microscope time–a true testament to her dedication and passion for furthering her field forward. Outside of the lab, she tries to maintain a healthy work life balance– “there are days when you have really those stretches of deadlines and long working hours, but then there are days where you can afford to relax a bit.” And she also tries to keep her weekends a little bit free these days, where she enjoys hiking, gardening, concerts, and trying local Atlanta breweries.

Das and her lab’s inspirational and innovative RNA imaging work is only just beginning, with many exciting discoveries awaiting, and a new understanding of what it means to make and store memories lies ahead.