What HIV Teaches Us About the Gut — and Ourselves

By Allison Pourquoi

Dr. Abigail Smith, PhD

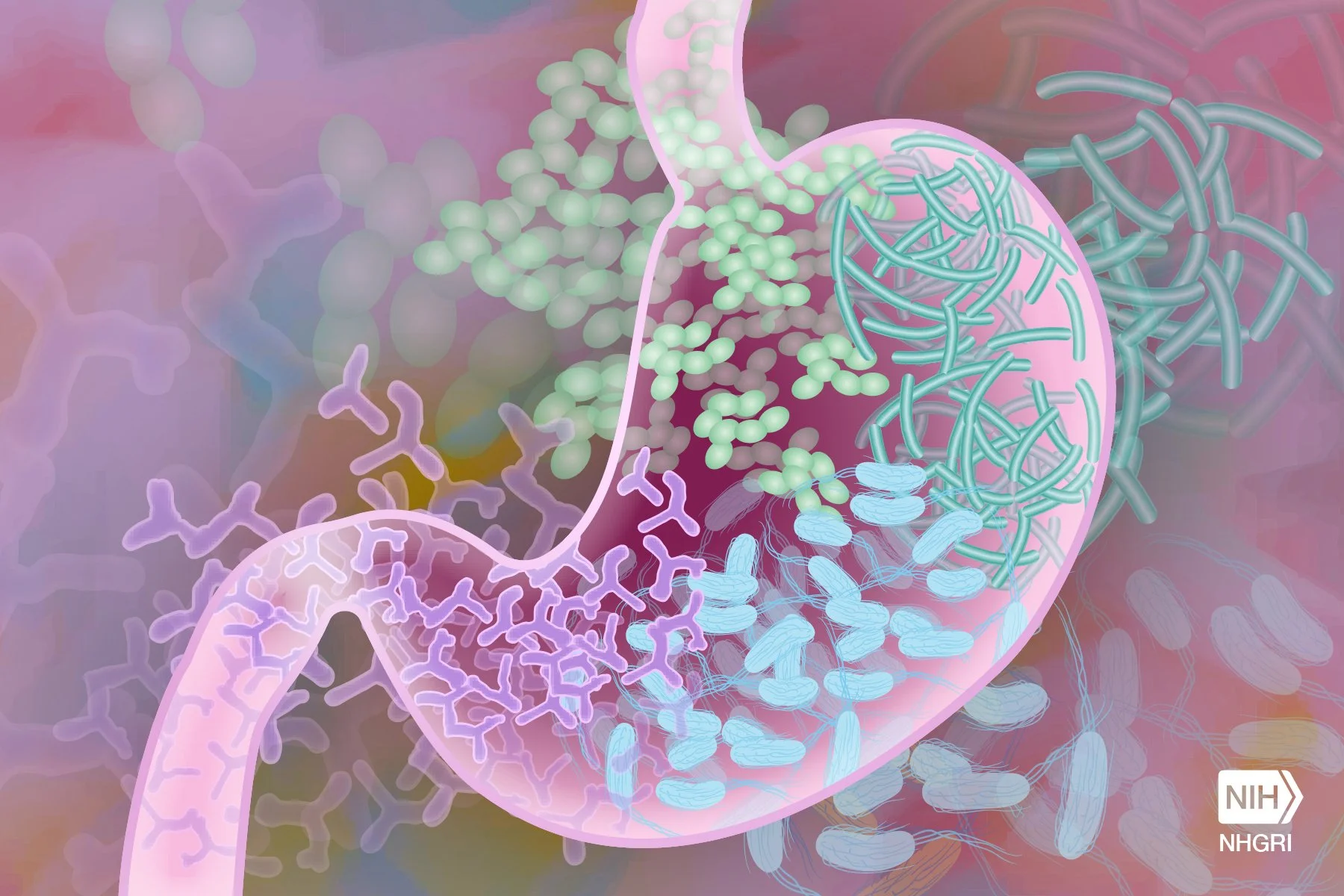

Most of us think of the gut as a digestive workhorse that breaks down our lunch, absorbs the nutrients, and occasionally reminds us that we overdid it on the hot sauce. But beyond its role in digestion, the gut is also a powerful immune organ. Nearly 70 percent of the body’s immune cells reside there, working alongside millions of microbes in a cooperative ecosystem known as the gut microbiome. This ecosystem helps to regulate inflammation, train the immune system, and keep pathogens in check. When the gut is in balance, we hardly notice. But when it is disrupted by stress, antibiotics, or disease, the effects can ripple throughout the entire body.

So, what happens if a pathogen such as HIV, the virus causing AIDS, disrupts the gut-immune ecosystem? This question drives Abigail Smith, a virologist and an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. She studies how HIV reshapes the immune system, especially in the gut, and why a subset of people living with the virus develop chronic inflammation even when they are receiving an effective treatment.

Smith has spent over 20 years studying HIV, from its molecular mechanisms to its clinical impacts. She has authored numerous peer-reviewed publications and continues to lead multiple NIH-funded projects at Emory's HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Unit and Center for AIDS Research. In short, she is not just contributing to the field of HIV, she is helping to define its future.

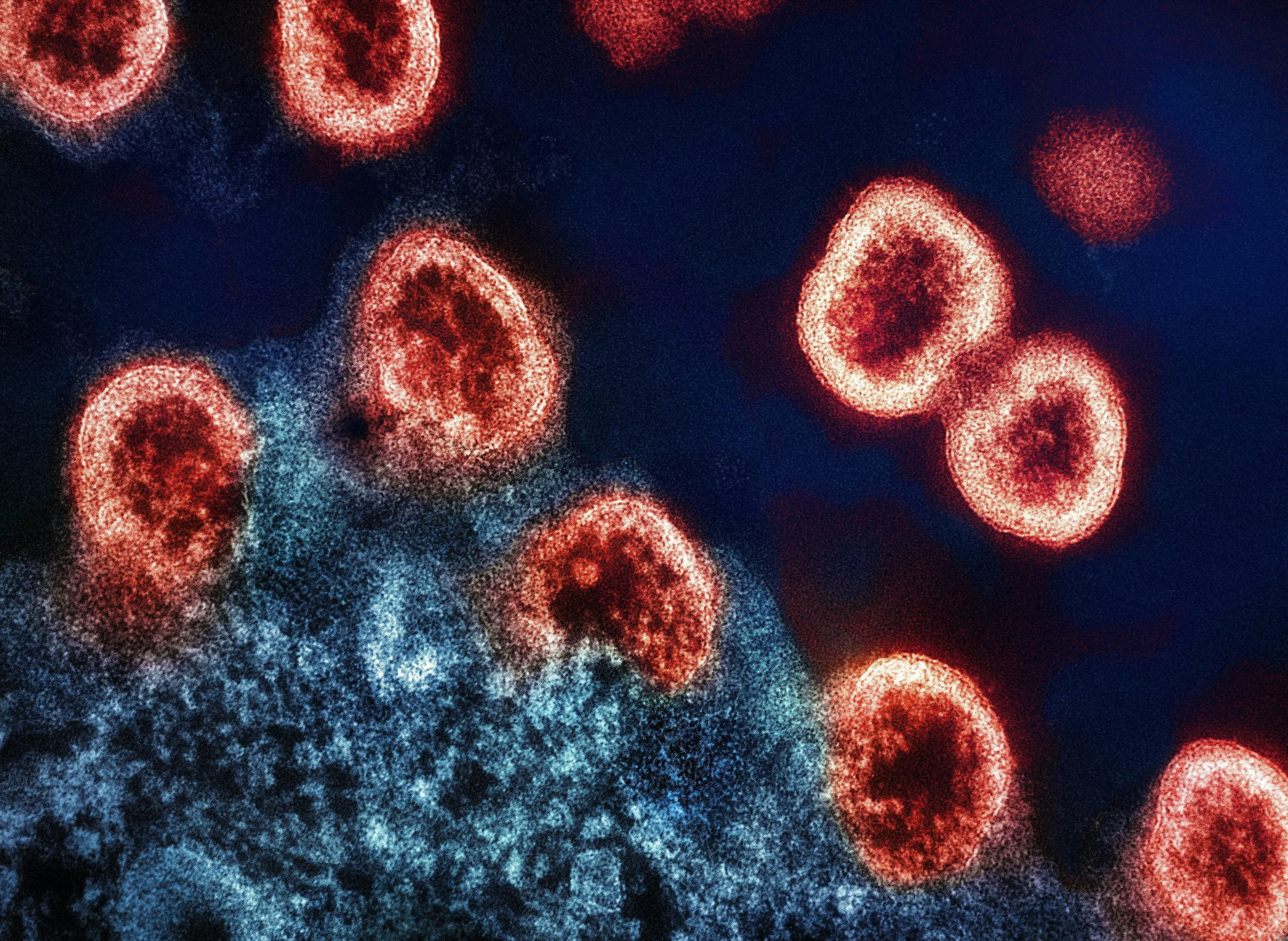

For decades, HIV research has focused on the presence of the virus in the bloodstream. Scientists tracked viral loads and observed how those markers changed with antiretroviral therapy in the blood. This research has saved countless lives but only tells part of the story. HIV does not stay confined to the blood; it targets the gut almost immediately after infection.

Image by Darryl Leja, NHGRI, NIH on Flickr

Because the gut lining is rich in CD4+ T cells, the very (immune) cells that HIV infects, the virus quickly damages this protective barrier. As a result, microbes leak into the bloodstream, triggering chronic immune activation and inflammation. This state persists even after viral suppression, contributing to long-term complications like cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, neurocognitive decline, and chronic fatigue. In other words, even when HIV is undetectable in the blood, its early assault on the gut can cause lasting harm.

By studying gut tissue—the source—rather than just blood, Smith’s team is uncovering how this damage begins. Her work challenges the idea that viral suppression alone is enough and suggests that improving long-term health outcomes requires starting with understanding the effect of HIV infection on the gut.

She also addresses another long-overlooked factor: sex and gender. Across many medical conditions, from heart disease to diabetes, researchers have found that sex-specific biology can influence symptoms, disease progression, and treatment response. But in HIV research, most studies include only cisgender men, leaving major gaps in the understanding of how the virus affects women and gender-diverse people.

Hormones like estrogen and testosterone play a central role in regulating the immune system, particularly in the gut. Critical insights are missed when scientists fail to study how HIV behaves in different hormonal environments. Smith's work includes cisgender women, transgender men and women, and others often excluded from clinical trials. She asks questions such as: How does hormone exposure shape the immune response to HIV? Why does inflammation persist more in some individuals? How sex or gender play a role in disease progression?

To explore this, her team collects small biopsies of gut tissue and observes immune responses in real-time, even by adding hormones like estrogen or testosterone to see how they influence immune activity. The results so far have been striking—immune responses differ markedly depending on hormonal context. These insights may help explain variations in inflammation, reduced immune function, and treatment outcomes, marking a step toward more personalized HIV care.

And the impact goes beyond HIV. Smith studies immune pathways that are also involved in chronic conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and type 2 diabetes. Her research could explain why these diseases often present differently across genders. Because gut inflammation also plays a role in colorectal cancer, her work may one day inform new strategies in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment. What began as a focused investigation into HIV has become a broader lens on immune health.

What truly distinguishes Smith's work is not just the science but the values behind it. She advocates for diversity in research in those who participate in the studies and even in those who design and lead them. Her lab is a supportive environment where young scientists—especially women, LGBTQ+ people, and those from underrepresented backgrounds—are empowered to ask bold, inclusive, and meaningful questions. She reminds her students that science is not just about finding answers; it is about expanding perspective. And the more perspectives we include, the better our science becomes.